Aspen Art Museum – July 29th – Dec. 18, 2016

Why paintings? Why make paintings that look like those made before? Why expend the energy to make, apply and remove paint and gesso, to harvest wood or fibers just to add more paintings to a world with a crisis of over-consumption.

Why paintings? Why make paintings that look like those made before? Why expend the energy to make, apply and remove paint and gesso, to harvest wood or fibers just to add more paintings to a world with a crisis of over-consumption.

And why live in Tokyo and fly back home to Mexico City and to Aspen, Colorado?

On August 4, we went to see a show of at the Aspen Art Museum by Gabriel Orozco. Meticulously hung in the spacious gallery on the 2nd above-ground floor, the show’s content is mostly new paintings.

The new museum building – opened in the fall of 2014 – is modern and the natural beauty of Aspen’s mountains is filtered out by four nearly continuous white walls. Windows are offset in little sitting alcoves and the line the entirety of the grand staircase that ascends steeply to the completely open-to-the-view, third floor cafe.

The new museum building – opened in the fall of 2014 – is modern and the natural beauty of Aspen’s mountains is filtered out by four nearly continuous white walls. Windows are offset in little sitting alcoves and the line the entirety of the grand staircase that ascends steeply to the completely open-to-the-view, third floor cafe.

The museum is free thanks to patron’s donations (Thank you Mr.& Mrs. Phelan).

The museum’s director, Heidi Zuckerman, curated Orozco’s show.

The curator’s tough job wasn’t physically hanging this show. The gallery is big and the paintings are all square, and a modest size. The artist began each one at the center of the square and painted and drew outward. The centers are all hung at the same height – so you can reach them, feel yourself working on them.

They are grouped by the method the artist used, so we can see the geometric paintings together, see the incised lines made in a deep black gesso surface, and then see shiny green tempura paint covering the surface of another group of paintings.

The installation is beautifully simple, and yes, that is harder than it looks. But hanging the show, isn’t the hard part of this curator’s job. Choosing an artist with big name recognition, who is articulate, handsome and not too full of himself is the key.

|

|

|

Aspen curator’s hard task

The director/curator made an excellent choice with the Orozco show.

The director/curator made an excellent choice with the Orozco show.

It opened a week of Art Crush – the major fund raiser for the museum – a big name, big price art auction that spreads out in galleries throughout the town and this year raised more than $2 million.

I want to live with these paintings – nearly any one of them. I question the wasting of materials and certainly hate waste for the sake of decoration. But I know I would get more of enjoyment from them than I do from my netFlix account. (One painting sells for more than 100 years of my current DVD plan).

So the answer to why Orozco is showing mostly paintings? To make money for the Aspen Art Museum, because Aspen is a place where people abide who have more money than they need to live, and will buy paintings that take months to make.

The outrageousness of the prices of Orozco work and other artists that donated work to the museum’s fundraiser bothers me not at all. The brilliance of the fundraising is its appropriateness to place and purpose – and of course its success. The prices allow the museum to continue to show interesting art, and for some artists like Orozco to make it.

What is still bothering me? I’m questioning why, with all the things I have to look at, I want these paintings.

Why do we want paintings?

Orozco has done very precise, almost mathematical, paintings for a while, but is known not so much for his paintings as he is for conceptual sculpture: a car sliced and reassembled, a whale carcass found and reassembled, an empty shoe box.

For a show at MOMA, he gave a case of oranges to all the tenants of an apartment building facing the sculpture courtyard. Some residents arranged the oranges in their windows and Orozco photographed this.

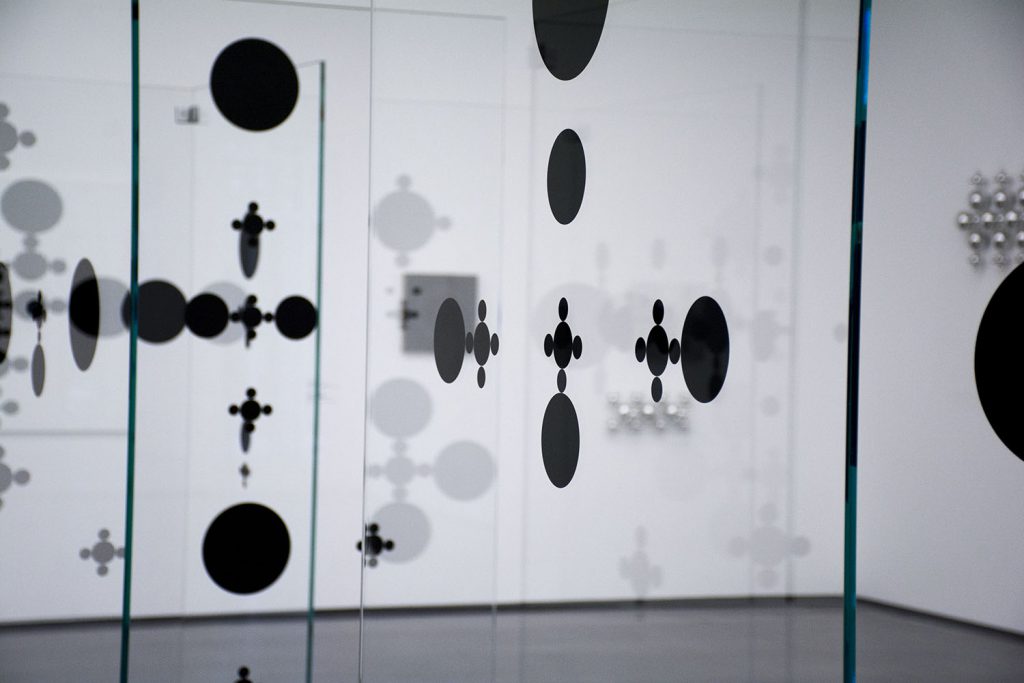

The sculpture in this show was made a year or so ago. Black dots obscure otherwise clear vision through large, doorway-size pane of glass. The dots reflect on other panes of glass and obscure the horizon, or the faces of people also looking at the paintings but the glass also defines the plane of the plum line. We like the openness of the Glass House, for example, the openness of a view through a window, but transparency is also dangerous. I know more than one person who has walked through a sliding glass door.

The sculpture in this show was made a year or so ago. Black dots obscure otherwise clear vision through large, doorway-size pane of glass. The dots reflect on other panes of glass and obscure the horizon, or the faces of people also looking at the paintings but the glass also defines the plane of the plum line. We like the openness of the Glass House, for example, the openness of a view through a window, but transparency is also dangerous. I know more than one person who has walked through a sliding glass door.

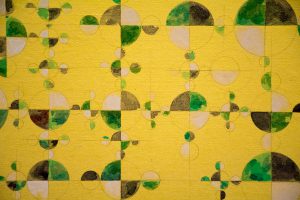

Orozco has the luxury of having always been known as an artist – both his parents were artists and his father was a well-known muralist. and maybe the necessity of needing to live as a foreigner somewhere that suits his careful process.  Somewhere like Tokyo, which is where Orozco lives and painted these recent paintings. One is a watercolor – with a delicacy that reminds me of traditional Japanese painting. This watercolor is in the style of paintings Orozco has made before. There is a formula, a set of geometric rules he’s following. He paints from the center outward and at each shape must make a decision about color. Color is practical, a way to define the system.

Somewhere like Tokyo, which is where Orozco lives and painted these recent paintings. One is a watercolor – with a delicacy that reminds me of traditional Japanese painting. This watercolor is in the style of paintings Orozco has made before. There is a formula, a set of geometric rules he’s following. He paints from the center outward and at each shape must make a decision about color. Color is practical, a way to define the system.

Why make paintings? His answer is about space and it is in sculpture. He treats the paintings like sculpture’s materials: carving into it, showing its depth. They have a back side, he said, even though we don’t see it. We can feel the thinness in this watercolor – the delicacy of the gold leaf.

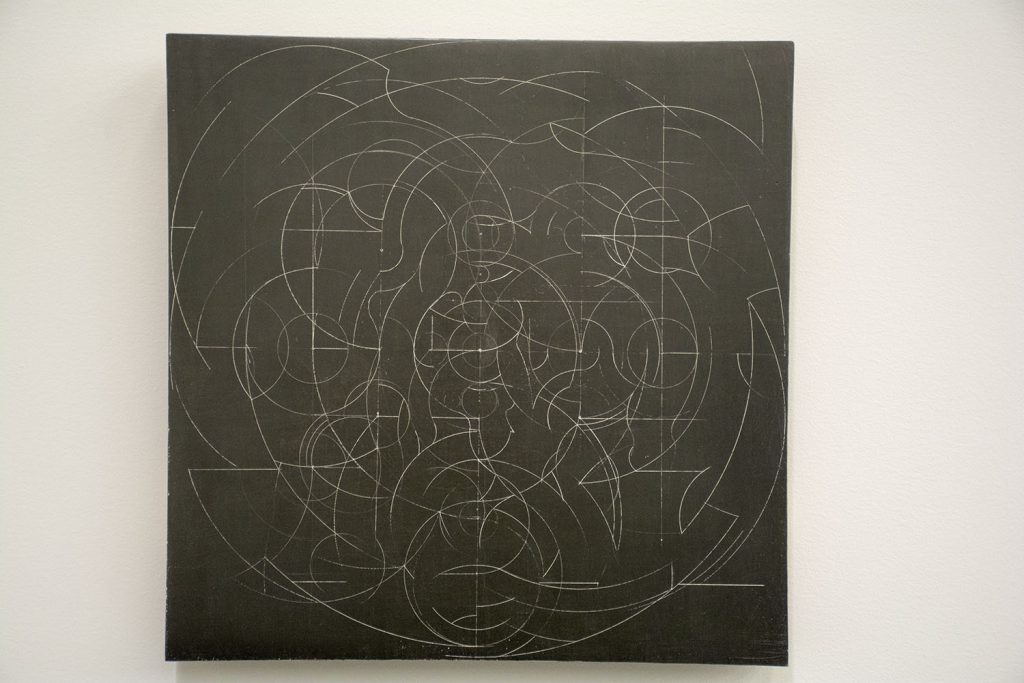

The black series have depth – Orozco’s marks are through thick layers of gesso and paint. His fine marks are scratched through with a compass, methodically. You can visually see the depth of the mark and the thickness of paint.

The black series have depth – Orozco’s marks are through thick layers of gesso and paint. His fine marks are scratched through with a compass, methodically. You can visually see the depth of the mark and the thickness of paint.

The surfaces of the green series (hanging along the long wall) are completely covered by a physically visible green, egg tempera paint. The green is scraped away to reveal an underlying geometric painting that are similar in form to the first series – like the watercolor.

The forms in these paintings are just a surface, a thin layer, but we can think about them as physically as we think about sculpture. By using different types of paint – oil below, tempera above – there is a visible tension of the materials. The layer below is complex but flat while the tempura shines like an egg white. And paintings can fool us into thinking there is depth: the landscape behind Mona Lisa, for example.

“After Mondrian,” said Frank Stella in Working Space, “abstraction stands at peril.”

Abstract painting has never played the games that diVinci and realistic painters were playing with illusion, unless you count surrealism as a form of abstraction. Even it went with most of abstract painting to a flatness, which 1950s critic Clement Greenberg so loved about Abstract Expressionism.

Abstract painting has never played the games that diVinci and realistic painters were playing with illusion, unless you count surrealism as a form of abstraction. Even it went with most of abstract painting to a flatness, which 1950s critic Clement Greenberg so loved about Abstract Expressionism.

We just saw a retrospective of Stella‘s work in Ft. Worth, and he is still an abstract painter. He was a minimalist and a post-Abstract Expressionist painter, but he’s been thinking about depth and Carravaggio. He’s over 80 years old, and still coming up with some wild ways to save abstraction from peril.

Orozco is going back to Mondrian to see if he can take it somewhere different.