— October 21, 2019 until February 2, 2020 — Denver Art Museum

I live in my own world of poetry and art. And what better friend for me to have in this world than the Denver Art Museum, just a 20-minute walk through beautiful Denver weather — one day 80℉ and the next day 14℉ — up Broadway past the petit camps of homeless folks, to the cultural center known as the Golden Triangle and bury my head in the sand of non-political art.

The art museum is an oddly triangular, post-Modern origami crane writ large. While it might be a joke told by a one-joke pony, I don’t mind that it is not part of a long, classical architectural tradition.

Inside are currently hanging more than 120 paintings by French painter Claude Monet in galleries that we know mirror the outside and are not straight up and down verticals, but which seem to have no architectural structure at all for this show. The walls are painted dark colors and spotlights make the paintings glow in isolation as if suspended from thin Colorado air.

This year of 2019, seems to be a time when it is easy to complain that the Queen Green City doesn’t need a gem of a show of old, Impressionist landscape paintings, particularly when the Rocky Mountains are just outside its ring roads, and the EPA is gutted and fracking is hollowing out the ground beneath us. It just seems too easy because these paintings by academy-trained, white and rich-in-his-lifetime Claude Monet are just too beautiful. And what are they doing for the homeless?

Monet is not doing Guernica, but what is Guernica anyway but a very cool composition by Picasso that he named for a horrific event. Joan Miro’s protest work of the same events is out in the world, too, and happened to be in a show at the DAM a few years ago and you couldn’t tell it from his other wonderful child-like paintings.

Every work of art is a political statement even if it doesn’t put its protest in its title. Monet’s painting of the Charing Cross Bridge would seem dated if it was called “My Life in Exile from the Franco-Prussian War”. And what more would it be doing for the homeless?

This show does political as much as most of what we see in the world, but it doesn’t pretend to have a political savvy that I don’t think we need to require in our art historians.

The show has been titled by its curators The Truth of Nature – this is a statement about what Monet was doing. Monet’s is not the work of a Bob Ross showing you how to paint nature making paintings that are never mistakes just happy accidents. Monet is not painting accidentally. He has a practice to paint the same or a very similar scene to try to give a true impression of how natural elements look to us. The work is about a life of perception how light works on things over the course of a day, through the year, over the course of many years and he is trying to acquire the skills to do this most truthfully.

I don’t know what pretext you could put on this show that would better help me go back out into the world after seeing it and figure out how to solve the homeless problem. But I do think we learn a lot about problem solving as we walk through fabulous hallows of a really great painter. One of Monet’s earliest painting is in the show, followed by landscapes made while looking at them on the Normandy coast. He’s learning to make paintings while Walt Whitman is writing Song of Myself, which we all see as a call for democracy in art, in government and a better America than existed in pre-Civil War America. Whitman doesn’t necessarily say anything but ‘be nicer to your fellow human, and love nature. ‘ Monet is giving us a reason to do so. To love the physical world around us, and give it some priority because as an environmental friend of mine says, once we destroy the wilderness, we can’t get it back to untouched wilderness.

I woke up this morning to read some poetry by Lyn Hejinian – another period of time I took off from thinking about how to solve homeless – that I followed by an even worst waste of thought watching a video about Renee Zelwigger’s plastic surgery and how good she might be in past films and, just coincidentally, a new movie.

Here’s a line from the somewhat chance poetry, or language poetry of Hejinian from her book called the Unfollowing –

“If nothing had a cause, cows could be hatched from robins and balls that fell on one day might float on another”.

I have been in my isolated world of work, family, art and poetry and am arguing that art made to tell a truth is valuable in any time.

If it is beautiful, I’m not complaining. Thanks, Monet, for making it as easy to look at as a well-made double play. I don’t think it’s a waste of time to watch kids play ball and make mistakes, but the beauty of doing it well is really a pleasure. How much artwork trying to say a lot doesn’t say enough?

I am trying to write poetry about Medicare for All, the current name for a country-wide healthcare network that pays every provider efficiently and is available to anyone who needs care. Bettercare for All – that should be the new name but no one will know what I’m talking about. If you could read poetry, would you know if it was good poetry? If I got to the absolute truth of the nature of our thinking about a way to pay for health efficiently? When paying for outrageously priced treatments is no longer a worry, people in other countries complain about the care. We are nowhere near that in this country. Old people complain about their Medicare doctors. Many people in America today, don’t even see a doctor, let alone know one’s name or their Angie’s list scores. How can we learn more about boring public policy ideas? Or what to think about them? Not from Renee Zellwegger gossip on YouTube.

How did Monet learn to paint nature so that it gave the feeling of time of day, quality of sunlight, make a case against man-made fog and war? Were the people of his time unable to read poetry about politics, or to see paintings like his and stop environmental degradation? Is it only in seeing them today that we understand the truth in nature?

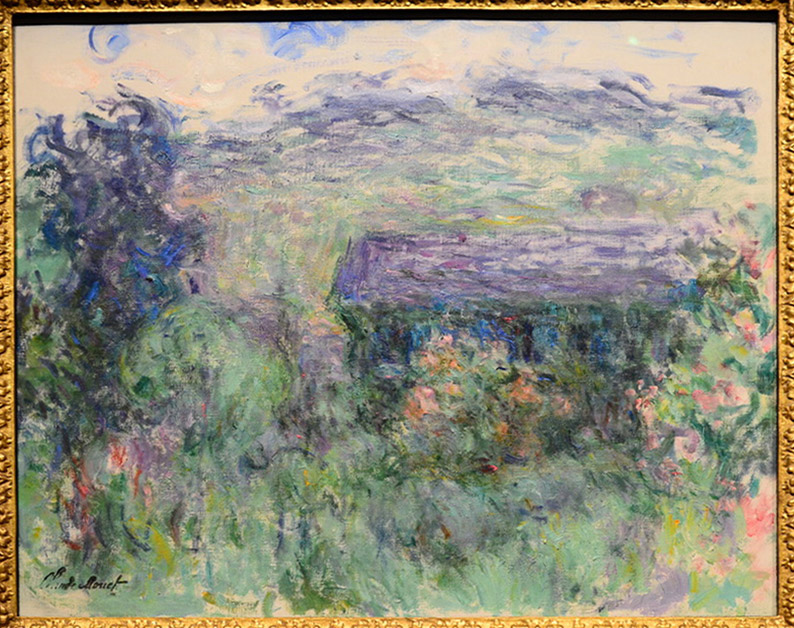

No ridgeline development – this is a concept in planning in place in progressive places like Telluride, Colorado but not in (formerly) Republican controlled Vail and its suburbs of Eagle County. There is a reason that good planning means you build a home below the ridge so that when we look at the line of the mountains we don’t have to look at your stupid dwelling. Can you see how hard it is to make out the cabin in this painting? He could have made the object more clear, as he did with the painting of two girls in a boat that sits next to this one of the hidden house. There is something being said here about the heavy weight of humans. And possibly ridgeline development.

What to actually do in the world requires artists of public policy and I don’t think we want our art curators to assume that role. We want them to show us some truth so we can figure what’s right and not confuse people with baseball and advertisements. Will you read poetry about healthcare, and will you take the time to understand it, and let you brain ponder ways to create an efficient universal healthcare program? You’d probably just like me to make an animation.

What if there is a better way to operate a computer or a car and we are not given the opportunity to try it because we are being sold a different system? Fill this question in with anything, better way to run public institutions like art museums, or whatever question you want. But take the example of all the people who adopted a computer in the 1980s. They were given, and pretty much needed to use, the Microsoft version of how to write text and do spreadsheets. Eventually, many found a way to the Apple system that was better designed. Every computer workers I know now uses a Mac. But that was a long waste of time.

We are moving globally to solar energy but when I talked to politicians in the previous two decades, no one though that renewable energy could be any more than 2%. We were thought to be crazy Coloradoans when we passed a law around 1999 for the state to be at 25% in 25 years, Now that goal seems low. When long ago, one Republican lawmaker from Grand Junction told me 2%, he had very good reasoning for saying so. He accepted the conventional wisdom. Maybe he should have looked at more art.

Accepting is the Microscoft problem. It’s why the polls are so wrong about every political issue. We wonder about an issue or candidate, and go to the media, listen to learn,and the media speculates about who is (speculatively) the most electable in our country for president. We can’t know the future; a reporter doesn’t know. They tell us the poll results. We listen as if they are news. And then someone calls us to take a polls, which will then be repeated back to us and we, if they are actually polls, are who told them the information and we – the respondents – don’t know.

Do you see why I think it is important to look at a good portion of a lifetime of work by one painter who was really trying to show something really truthful?