Enter Redline – a contemporary art space in Denver – and swim through years of work by Judy Chicago, who having reached the grand old age of 75 is this year being feted with several retrospectives across our country and whose name is by now known to people who have some knowledge of contemporary art; pull long, breast-high strokes through the minimalist, slick, translucent lacquer paintings of the early ‘70s, past any reference to dinner plates from the famous Dinner Party piece to the back wall where Chicago’s long canvas about the history of the 20th Century rests, The Fall, luring in viewers with drawings of Hitler and witches.

Of course, I didn’t actually swim through this show. I got sucked in by the first piece which was a box of prints. Redline is still hanging shows like a traditional gallery so the box was opened and tucked away somewhere and all the pages were pulled out and hung in order on the wall. And of course, they didn’t want us pawing over the prints. They are beautiful. The boxed set is Chicago’s self-retrospective and each print is about a period of her life’s work. Oh, the simplification … so well done a politician would be proud.

On to the next work, Chicago again precisely places on the canvas stuff that will thoroughly interest me and I read four short paragraphs from what could have been her journal while she was painting the 12 discrete squares that were on the canvas regularly spaced, with the intriguing words squeezed around them.

And then beautifully crafted bronze and glass sculptures of a man’s head – many of them. All are made of easily breakable glass that is hard in its coldness compared to the warmth of the oh-so-durable metal alloy that can so easily take a patina and make vivid colored eyes. I’ve never seen bronze castings that are this lively, in a post-modern matter of fact kind of way. They aren’t the sad eyes of dogs or Rodin’s figures. These heads are of the guy next door and he’s got some stuff on his mind, too. But that’s for you, his neighbor, to discover. Chicago is just going to give you a hint with a title like “Two-faced Man.”

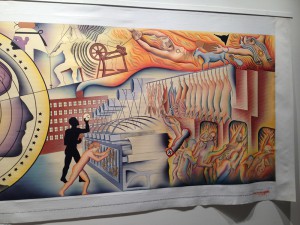

I suggested the trip through this exhibition was like a swim – lots of physical stuff slowing me down because it was either interesting or beautiful, but I fell entirely in the world of this work, on the back wall. This long painting, the history of humanity, The Fall. We’re told by curatorial notes that this painting and others in its series (called Holocaust Project) took years to make and was catalyzed by a trip Chicago and her husband took to holocaust sites in Europe. Why would we still be having holocausts? – the notes purport to be the artist’s inquiry. And I felt compelled to take in this panorama of the history of human badness.

The painting is a jumble of icons that the painter must fit on this long canvas, 3-feet tall so it all fits at once in our view, and is trimmed at the bottom with words. It is a struggle to take in all the pieces and reassemble them to give (new, helpful, insightful, emotional) information to our brain about this big subject – like the French structuralist philosopher Roland Bathes said in his essay about the Eiffel Tower – to make memory and sensation collaborate to make a simulator (of Paris, he said / of the history of the Holocaust, she says).

This Bayeux-Tapestry style of history isn’t our normal view in the 21th Century; information is rarely all laid out before us on one canvas just as the city of Paris rarely appear as it does to those viewing from the Tower. A bird’s view is not our ordinary one, and so we work hard to put together the landmarks as we usually see them.

Words are how we usually learn history. The words at the bottom of Chicago’s history are hard to read – above and through them, colors are vibrating against one another – I get sucked into the wheel of the ideas of witches pushed into the flames, workers shoved into factories and Jews to the gas chambers. When I step to the end of the painting, I want out, but I’m fixed on the painting, lost in it, alone. When eventually I look up at the stark and bare structure of the interesting art space that is Redline, I see an open studio door with no work going on inside. And I get a feeling of peace. Most of the other white, minimalist, self-hiding studio doors are shut and nearly imperceptible. Work may be going on inside, who knows. It is a feeling of visual relief. I am free, in a quiet, video-free, gallery space and there is more Judy Chicago to see. And it’s fun stuff.

A wall of drawings for the dinner plates, big sketches of a couple of plates, those plates themselves and more information about The Dinner Party fill the gut of the open Redline gallery. It is here that I want now to come up out of the water. I feel the weight of her years of work and I know that soon technology will encourage it, and I could have a drink delivered, in a spill-proof cup in respect for the art, and this art-viewing experience will become closer to real life. We shouldn’t be expected to walk through art like this. There should be art-side service.

Experience: Surveying Judy Chicago: 1970-2014, Redline Gallery, 2350 Arapahoe, Denver, Co – October 17 – December 28, 2014