At the Fulginiti Pavillion Gallery for Bioethics at the University of Colorado Medical Campus

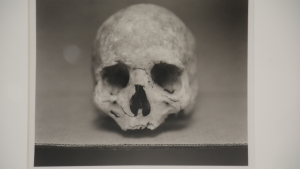

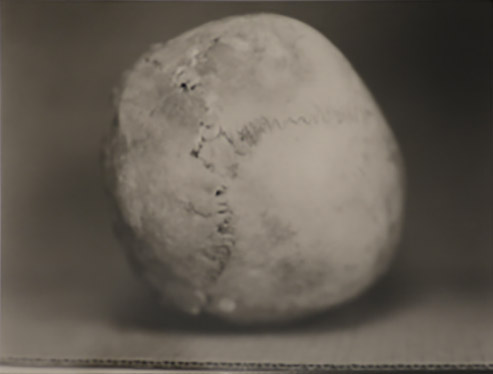

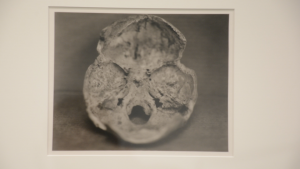

Denver – Photographs of skulls dominated by intense detail: the cracks that we know existed when we were infants reappear after death. After nearly a century in the ground the bone still shows evidence of being alive with elaborate texture like skin or leaves or wood. Description placards next to each photo describe in anthropological term the age, sex and condition of the skull – all of which were found on the grounds of a former insane asylum in Colorado. They and the rest of their skeletons were discovered in an unmarked grave in 1993. They had been cleaned but as the remarks indicate there was staining from the dirt. Some had been cut, broken, pegged or taped together.

Denver – Photographs of skulls dominated by intense detail: the cracks that we know existed when we were infants reappear after death. After nearly a century in the ground the bone still shows evidence of being alive with elaborate texture like skin or leaves or wood. Description placards next to each photo describe in anthropological term the age, sex and condition of the skull – all of which were found on the grounds of a former insane asylum in Colorado. They and the rest of their skeletons were discovered in an unmarked grave in 1993. They had been cleaned but as the remarks indicate there was staining from the dirt. Some had been cut, broken, pegged or taped together.

It was obvious that they had carefully been placed within the view of the camera lens and that they would sit still for the exposure of the black and white negative. You can imagine the photographer and the scientist, who wrote the placards, discussing each subject. You can imagine the skull being rotated to get a better view of a detail. And you can imagine the click of the shutter when it appeared this subject was in just the right place.

It was obvious that they had carefully been placed within the view of the camera lens and that they would sit still for the exposure of the black and white negative. You can imagine the photographer and the scientist, who wrote the placards, discussing each subject. You can imagine the skull being rotated to get a better view of a detail. And you can imagine the click of the shutter when it appeared this subject was in just the right place.

The detail at the center of each photograph was intense but as the form retreated from the picture plane the focus softened. Often this makes the skull seem to glow at the edges in a field of ether that we commonly recognize in black and white photographs. You start wondering about the camera equipment.

The photographs were taken by Andrea Modica, and are owned by the Denver Art Museum, we learn from a beautiful brochure, and from a discussion between the photography curator at the DAM and the curator of this exhibition. The artist titled this series of photographs, Human Being, at about 50 of them are currently on view at a new gallery space on the CU medical center campus. Part of the Month of Photography Denver, this show runs from March 5 to May 14, 2015.

The photographs were taken by Andrea Modica, and are owned by the Denver Art Museum, we learn from a beautiful brochure, and from a discussion between the photography curator at the DAM and the curator of this exhibition. The artist titled this series of photographs, Human Being, at about 50 of them are currently on view at a new gallery space on the CU medical center campus. Part of the Month of Photography Denver, this show runs from March 5 to May 14, 2015.

The camera used was a 8×10 inch view camera, which makes a negative the same size as the 8 x 10 inch paper on which it was printed using the platinum process. This process is an old one, and means that the artist hand painted a metallic, photo-sensitive solution on paper, sandwiched that paper against the glass negative, kept it in the dark until exposing it to a strong light, and then developing the image with chemicals that allow the exposed to rest on the paper and the unexposed to wash away.

The skulls in this Human Being series are given plenty of space in the 8 x 10 inch environment, so they appear smaller than life size, a little precious. They’re arranged at an average person’s eye level so they are much more in our field of vision than the placards of details which are below them and off to the left. This kind of attention to detail filled the discussion of these works as people talked about the associations we make to skulls and carefulness.

The dead body of the person who thought in these skulls wasn’t identified, or given a careful treatment 100 years ago. After being discovered in 1993, that treatment changed. A forensic anthropologist, Michael Hoffman, carefully cleaned, studied, categoried, diagnosed when possible and stored each skeleton. Then the photographer, Modica, carefully arranged each skull within her viewfinders reach and used a tedious, archaic method to document at least 33 of them. They sat still for this, and so the results are beautiful. Photographing the people who lived in the Colorado insane asylum 100 years ago would not have been so easy. They were nuts. And they might not have appeared so beautiful.

p.s. It’s also hard to find Hoffman’s work on this subject – not google-able. It is interesting how shallow our attention is.