Georgia O’Keeffe and Contemporary Painting – MCA Denver Feb. 15 – May 26, 2019

A few paintings by the canonized artist Georgia O’Keeffe hang with new paintings in the clean modernist galleries of the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art.

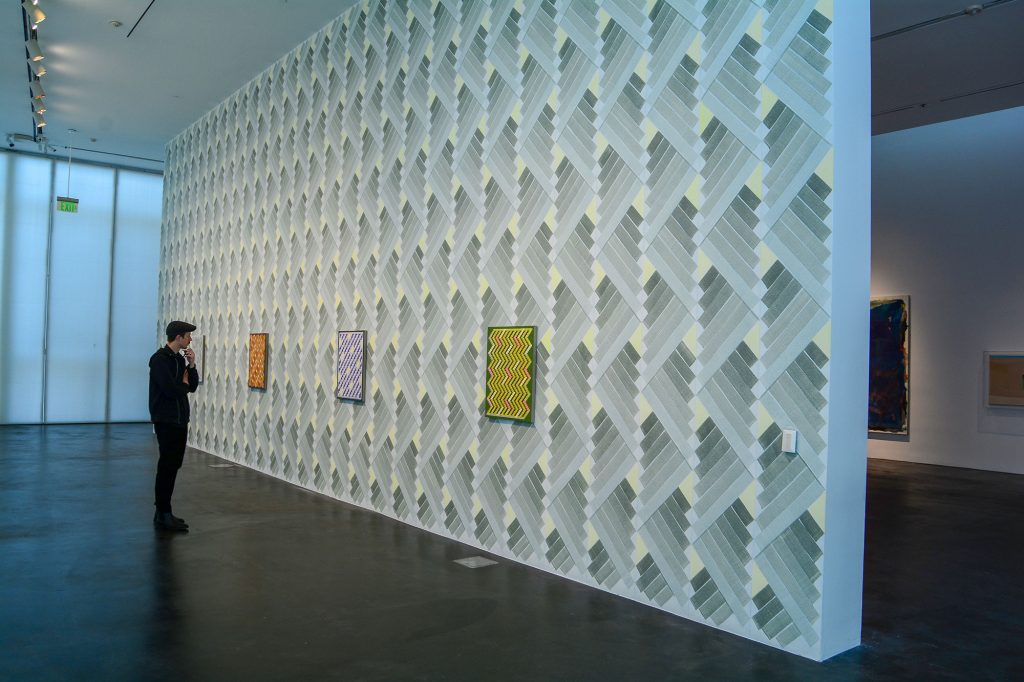

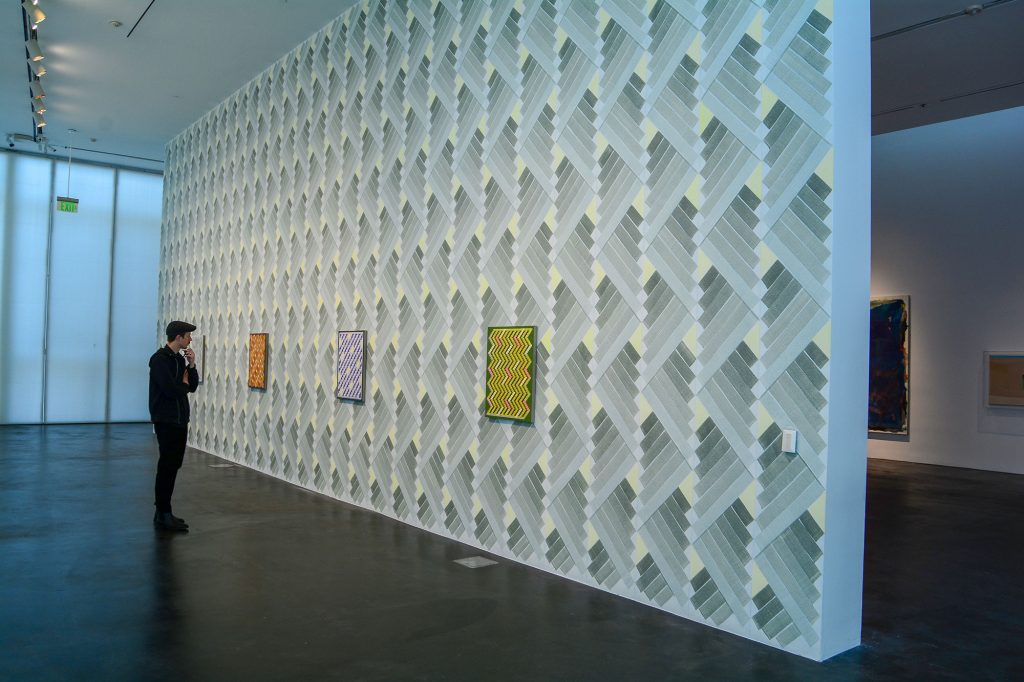

The premise of the show is that the contemporary artists have learned something from O’Keeffe – even if it is just a palette choice, or sparsity of line. Take the work of Melissa Thorne, who covers a wall in the museum with pattern. On this wall hang her measured geometric paintings. No modeled forms with slightly veiled sensuality jump out as an O’Keefee after effect, but strong stokes of just the right viscosity feel like a Georgia wash.

More than walking around the gallery wondering why this or that could have been inspired by O’Keeffe, I am affected by the experience of having looked at many Georgia O’Keeffe paintings before seeing these. I’m already know how to look at the contemporary works. It’s like I’ve already seen Breaking Bad so I can get into the prequel more easily.

Three of us who have each looked at a lot of O’Keeffe’s stood in front of a painting by Lesley Vance. Each one of us had picked it as a favorite. We took turns standing away at about this same distance from it, knowing that this is an intimate painting like so many we’d already seen by O’Keeffe and hanging elsewhere.

Each of us mentioned things that gave a pleasure: an aesthetic pleasure similar to tasting a peach. And that was the tasty feeling was what I felt about the curl at the bottom left of the central white form. The presence and formfulness of this white object is so strong I could also imagine the smell of fresh pressed linen. And this particular aesthetic experience was replayed for me later, when linen wafted off a glass of Chardonnay.

The painterly modeling and subtle shadows fool us into feeling the forms are taking shape in front of us. I look at the painting and can imagine the smell of dough making its final rise into a fresh baked loaf. The rich green background takes me to the silence of a grand old library where I have been long seated in a comfortable chair with that silence speaking to me from words on a page. It’s velvet nappiness is that sound of the turn of an onion thin page. This painting is sensuous and not because it mimics the outline of anyone’s sex organs.

I have a friend who paints oil on large canvases with lush strokes that currently represent aspen tree forests. She’s been painting since the nineteen-sixties — not always trees — but stubbornly in oil and lushly. Everyone around her who was knowledgeable about art would tell her that she was wasting her time because painting was dead. Conceptual art had become the more meaningful form for art to take – being the non-retinal art that Marcel Duchamp advocated – and serious artists were suspicious of eye candy. Certainly no one wanted to be sentimental. Surely O’Keeffe was charged with that. But please, she’s no Norman Rockwell. I think she was brave not to fall into the surrealist solution and add a melting watch to claim to paint the reality of dreams.

Painting may be less dead that it was post-conceptualism, but it still struggles to be meaningful, to convey powerful ideas, as Duchamp wanted art to do. My friend the oil painter who ignored everyone who told he to quit painting in such a beautiful way, said with certainty, ‘Painting won’t ever die because we love looking at it.” And she’s right. I love getting this sensual, effervescent – the aesthetic experience.

I love it when I’m looking at the tattoo artist, Amanda Wachob, whose show co-habitats the MCA currently, and the vivid ground on which tattooed images were applied. As I climbed the flight up to the aesthetic beauty here in After Effect I’m still thinking about surfaces. O’Keeffe’s is generally non-textured. Her paint is even somewhat thin, laid on a Gesso-ed canvas that was polished smooth before any paint was applied. It is almost mimicking photography, which always disappoints me with its glossy thinness on a thin surface. My appetitious human nature wants a surface with some life of its own as well as all the sensuousness of these painterly techniques.

Corey Drieth’s paintings give me that texture that I’m a sucker for. And one piece in particular, a diaphanous one onto wood – reminds me of a tattoo. The wood grain comes through like skin in one of Amanda Wachob’s watercolor tattoos.

And hanging along side these small square works is a very small O’Keeffe. It is framed by a bit of fine car chrome and then set on a board doubling its area and framed again in silvery, rounded wood. I can imagine it hanging on an adobe plastered wall in a softly curving New Mexico living room.

The O’Keeffe-ness in each gallery continues to remind me, the viewer, to allow the work to be intimate. I looked up Lesley Vance, later, and found a gallery in Belgium that shows her work, and they almost gloat over the fact that they are small and the gallery gives them a whole wall. In this show, these are a few newer paintings where Vance tries to get bigger, and she seems not yet to have figured out how to get that same sensuous experience to exude from the canvas. Likewise, the beauty of the Drieth paintings would diminish if twice the size. Enter Leslie Smith III whose work tries to do O’Keeffe on a large scale.

For the red line alone I’d have this painting in the foyer of my world headquarters, if I had one. This painting has a presence, yet I’m not convinced that Smith does a full O’Keeffe any more than Vance does when scaling up. Another artist in this show, Loie Hollowell, starts with a 3-d canvas. They aren’t as big as the Smith piece, but I feel I need to step back. Her work needs the illusion that distance gives to exude the sensuality we associate with O’Keeffe. Up close the 3-d elements are hokey. At a distance, she needs more scale. Photos of these are almost better than the paintings, and that’s not really a good thing.

Artist Jeffrey Gibson has a few pieces in this show as well, hanging on the wall outside the inner galleries. I can’t step back from them because I’m in a hallway, essentially. This distance gives me a great view of the Native American bead work on the bottom of the piece, but I don’t get the velvet quilt feeling that I got from similar paintings at the Denver Art Museum last summer.

Just saying ‘velvet’ makes me feel guilty, not to mention all the gushing I’ve done in this piece about painting’s lushness. Duchamp’s knowing smile appears in my head, warns me I’m falling for the decorative, the sensuous, the retinal sugar. But as he said about himself when he made ReadyMades that were pleasant to look at – ‘nobody’s perfect.’

Corey Drieth

Leslie Smith III

O’Keeffe & Drieth

Melissa Thorne

Lesley Vance