Denver – July 10, 2014.

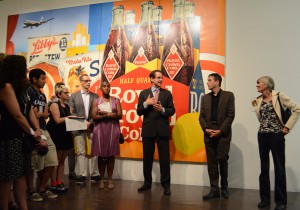

You have to be inhuman to not GET an artist when you see a good retrospective. When you see the work of Tom Wesselmann at the Denver Art Museum this summer you’ll get the classic, chronologically ordered line up of this Pop artist’s first work, the work that made his reputation, and then some of the best examples of those works. And, if this was a classic retrospective, you’d see later attempts to try to perfect the classic stuff, and understand thorough this artist’s process and GET it.

You have to be inhuman to not GET an artist when you see a good retrospective. When you see the work of Tom Wesselmann at the Denver Art Museum this summer you’ll get the classic, chronologically ordered line up of this Pop artist’s first work, the work that made his reputation, and then some of the best examples of those works. And, if this was a classic retrospective, you’d see later attempts to try to perfect the classic stuff, and understand thorough this artist’s process and GET it.

Wesselmann’s later works are actually very different from what made him a famous POP artist. The middle periods show a divergence from mainstream art and I’m really wanting to learn more rather than say “I get it.” Maybe that’s why the show is called Beyond Pop.

Wesselmann’s later works are actually very different from what made him a famous POP artist. The middle periods show a divergence from mainstream art and I’m really wanting to learn more rather than say “I get it.” Maybe that’s why the show is called Beyond Pop.

Like many artists associated with the Pop Movement, Wesselmann became an art commodity at a young age and could produce a lot of big work by finding shortcuts – Warhol used silkscreen printing to produce copious amounts of work, as well as a factory of artists to do the manual work, others used techniques from billboard painting.

Wesselmann, who had been making a living teaching high school math, re-purposed commercially printed billboards to make his most famous large paintings of women, cars and Wonderbreads. He collected the imagery, pasted it to large canvases and then drew and painted around it. His pop sculptures of kitchen or bath vignettes are made of real stuff. All of this early work use images that place them squarely in the time they were made, and now, that’s a while ago.

That this show evokes nostalgia may be a failing of Pop Art. I walked through this early works in this show with a guy who is an incredibly meticulous painter and I got the feeling he scorns the Pop Artist’s shortcuts as lazy. “It’s like a catalog of the 60s,” he said about the show. Nostalgia would not come into play if this was a retrospective of any of the artists in the period before Pop – from a Rothko, or a Jackson Pollock show. But Pop Art used the image of its time, and now with time, it’s nostalgic.

The Abstract Expressionists (like Pollack and Rothko) sifted out images that would give away their time period – abstracting images to the point of unrecognizability, abstracting to marks on a canvas that are nothing more than evidence of their having been made.

Wesselmann’s wife was walking through the show with me (and many other lucky members of the press) and she explained the post-Pop phase of her husband’s work as a swerve to and from abstraction (with long stretches in figuration). When I asked, she gave a definition of abstraction in visual art – anything made from a mind and a hand – so succinctly and quickly I still assume it is a definition they both shared, like the terms in a manifesto universally known to all the artists in the cadre.

The Wesselmann definition comes from Abstract Expressionism, or Action Painting as it is sometimes called. The abstraction in Abstract Expressionism is a final-state abstraction, something that comes directly from the mind producing something tangible even if it is just splatters on canvas. Abstraction technically is what every artists does – abstracts (takes from) some image to make another with focus and emphasis on what the artist wants to illustrate. Impressionists abstracted images by focusing on light, Cubists on the 3-dimentional aspects of objects and Abstract Expressionist abstracted away all recognizable objects until all that was left was a painting.

The Wesselmann definition comes from Abstract Expressionism, or Action Painting as it is sometimes called. The abstraction in Abstract Expressionism is a final-state abstraction, something that comes directly from the mind producing something tangible even if it is just splatters on canvas. Abstraction technically is what every artists does – abstracts (takes from) some image to make another with focus and emphasis on what the artist wants to illustrate. Impressionists abstracted images by focusing on light, Cubists on the 3-dimentional aspects of objects and Abstract Expressionist abstracted away all recognizable objects until all that was left was a painting.

The work Wesselmann made after the recognizable Pop stuff, Mrs. Wesselmann said, bounced between abstractions and figuration, and finally returns to the first work you’ll get to see in this show – the great American nude in a series he called Sunset Nudes.

The work Wesselmann made after the recognizable Pop stuff, Mrs. Wesselmann said, bounced between abstractions and figuration, and finally returns to the first work you’ll get to see in this show – the great American nude in a series he called Sunset Nudes.

If the word abstraction has turned you off, let me explain more clearly and I think you’ll come back happier. Wesselmann’s earlier nudes are classically nice drawings of the female figure. He experiments with ways to make the drawing more present that a drawing, and he does this without relying on virtuosity, which artists have been developing like carpentry skills since Modernity began. When he veers to the ‘abstract’ these later works are a very realistic representation of things that just aren’t that recognizable. Their subject just happens to be marks he made earlier – drawn lines, for example. He makes these images of drawn lines ultra realistic – by cutting them out of metal. The lines become objects. So, in reality, their is nothing abstract about Wesselmann’s work. Sorry, madam.

Another group of works, which I think Mrs. Wesslemann must be referring to when she thinks ‘abstract,’ was created in a similar way. Wesselmann was painting the steel forms that were made from his drawn lines and used Mylar to mask the sections that he didn’t want painted. He’d pull the mask off, put another one on that exposed a different section to paint. This wasn’t action painting – he wanted the grass lines to be green, the sky lines to be blue – it’s classic realism. The scraps of Mylar that were left on the studio floor were weird shapes of beautifully colored Mylar. By collaging them, he made some Matisse-like dancers and added other colored shapes. The result is an abstraction of Matisse’s later-life collages. Wesslemann then does a Pop thing to the little Mylar collage – he blows it up to super size and cuts it out of metal.

Another group of works, which I think Mrs. Wesslemann must be referring to when she thinks ‘abstract,’ was created in a similar way. Wesselmann was painting the steel forms that were made from his drawn lines and used Mylar to mask the sections that he didn’t want painted. He’d pull the mask off, put another one on that exposed a different section to paint. This wasn’t action painting – he wanted the grass lines to be green, the sky lines to be blue – it’s classic realism. The scraps of Mylar that were left on the studio floor were weird shapes of beautifully colored Mylar. By collaging them, he made some Matisse-like dancers and added other colored shapes. The result is an abstraction of Matisse’s later-life collages. Wesslemann then does a Pop thing to the little Mylar collage – he blows it up to super size and cuts it out of metal.

And if realistic work about lines and collages feels too abstracted, Wesselmann’s next and final series is a group of paintings of nudes again, the Sunset Nudes. They are more of the great American nude he tried to made in the early 60s, just as Hem and Fitzgerald were trying to write the Great American Novel. The style of these paintings is bold and collagey, and follows directly from the Matisse-like imagery that is exhibited right before it. Matisse was an obvious influence.

And if realistic work about lines and collages feels too abstracted, Wesselmann’s next and final series is a group of paintings of nudes again, the Sunset Nudes. They are more of the great American nude he tried to made in the early 60s, just as Hem and Fitzgerald were trying to write the Great American Novel. The style of these paintings is bold and collagey, and follows directly from the Matisse-like imagery that is exhibited right before it. Matisse was an obvious influence.

At the end of the chronological walk through this show, I wanted to see more of Wesselmann’s work. And maybe that was the aspiration of the curators of this show, people involved with the Wesselmann estate.

I walked back to see some of the work, and kept trying to find a way to get back farther from some of the greatest, largest ones, but always hit a wall. I walked back to previous galleries so I could look through and see one with some more distance. It wasn’t perfect, and I watched several people slide by without getting what was going on.

I walked back to see some of the work, and kept trying to find a way to get back farther from some of the greatest, largest ones, but always hit a wall. I walked back to previous galleries so I could look through and see one with some more distance. It wasn’t perfect, and I watched several people slide by without getting what was going on.

Maybe I’m just being nostalgic for the good old 70s, but I had this sad longing for a museum with enormous white walls and vast interior spaces designed to show Pop Art and other abnormally large work like Minimalism, a period which followed Pop. I wanted to walk into a different, old-school gallery where the paintings of Mr. Wesselmann could overwhelm me. I wanted to go back to when the Denver Art Museum was new and boldly showing big exhibitions of the relatively new Pop Art, entire shows dedicated to the work of Claes Oldenburg and James Rosenquist.

I wanted to transport this entire show to the Stanton Gallery – the beautiful white box that was the gem of the museum in that old building – the Ponti building (the one named for the architect, not the donor). But the Stanton Gallery is already in use – as a storage shed – so it can’t be done.