New Mexico Museum of Art – July 23, 2022 – January 8 2023

Transgressions & Amplifications: Mixed Media Photography of the 1960s & 1970s

January 15, 2023

I was fascinated by this organized collection of work — mixed media, yes, and very mixed — that I read as a cry from fifty years ago from artists walking the cutting edge of photography. After an hour in the show this past November, with so much detail packed into every case and on every wall, I knew I needed more time. I wanted to return this weekend and see it again with friends who are artists, one an RIT graduate and life-long professional photographer. But the show is over. I’m bummed because I wanted to just bring in other artists and overhear the comments they might make aloud while looking. But too late. Closed last weekend.

I lived through the 60s and 70s, although was a child in the first decade. I learned in school about photography as a fine art: Ansel Adams and other nature photographers from the B&W era. Since my school wasn’t very art oriented, I am guessing everyone knows Ansel Adams or someone like him. By the 60s, those photographs were accepted as fine art. Commercial photography was everywhere then. Color printing easy. Fashion photography was fabulous and pushing all kinds of design boundaries, so photography as art was a little stunted by its more obsequious (and obstreperous) relatives, the commercial stuff.

Still, photography was tied to representation – having replaced painting a hundred years earlier as a document of the times, we counted on it to document the world. No longer did we set something in stone but in a full-color print. In many middle-class homes, starting in the 50s, the art on the wall was a photograph of a painting. Blue Boy printed on a textured board, framed and now sold at Target, etc. The use of printed images is so common that people don’t even notice it. The floor I’m standing on is just a picture of wood printed on a click-together plank of cork.

When we, Terry & Steuart, became art-school students in the 1970s, we knew we must have a camera to document our work. In fact, our first partnership was a camera purchased together with a signed contract between us for its use and dispossession if needed. It was stolen, years later while on vacation at Copper Mountain after we had signed a marriage contract that superseded the quaint partnership agreement. Our next camera, and the next ones are in a box under the bed. Photography is not longer physical. It’s digital.

The subject of this show is the relatively short history of photography from its first becoming cheap to produce and being everywhere to its de-professionalization and over-saturation in the digital era. The work included is from the 60s & 70s, so the makers don’t know the future. But somehow they knew they needed to do something to inflate their work away from the thinness of a modern photographic print, to do something more than print the beautiful image on a textured board and frame it for Target to sell, cheaply. And if small, a print was intimate, not something you shared on your phone. Blurry was not yet hip.

In all these artists’ lifetime, painting became non-physical – a thin surface that in the 50s was praised for its flatness. As I studied art history, I could see how painting went from a realistic picture of (the artists interpretation of) real life up to this point where flatness becomes the thing, and then color, as well as space, goes with Ad Reinhard’s black paintings and Robert Rauschenberg’s all white painting. (The same progression has taken place with jigsaw puzzles. You start with Thomas Kincade and then go for monotonality)

And then, as I learned in art school, painting was dead.

In studio classes, we didn’t paint, but were involved with art making that involved a lot of process. I worked mostly in printmaking and Steuart in sculpture. We both learned to cast metal in sand or lost-wax methods. Works made in technical media had something you could relate to the real world, if not texture or weight at least a process. And those real things, grindings marks on metal, the embossing of a black ink line from the itaglio plate, could be discovered if you looked and knew enough. Even the nuances of a black and white print made by hand in the darkroom.

Art made with human ingenuity, this physicality of technique, finding out the How-Done-It wasn’t enough of a benefit to counter the ecological debt. We started making temporary public art. In one piece we used dead and down Lodgepole pines arranged into a visual statement. After being on view for a summer, these trees were easy for forest workers to clear away and make the land less a threat.

From the 1960s on, we have all become more aware of the problem of art (as well as everything else) as ecologically burdensome. We talk today about data storage problems, but if you make art, you have a bigger problem in having so much real stuff you have to store. Because, really, when is it interesting to look at your old paintings? When is it interesting to look at a painting? And for how long, really?

In the 1960s, art as ‘happenings’ was the hint that art was becoming ethereal, just as photography was becoming digital (although we didn’t know it yet). Conceptual art could replace old boring paintings on the wall. New stuff to see and experience at little ecological cost. Where did this place photography? Hang one on the wall? Boring as painting. Screen savers and wall paper that randomize, change all the time. We get bored with beautiful, realistic imagery As soon as this became obvious in the 60s, artists starting thinking what they could do with paintings or photographs to yell something like “a human is here, trying to say something with this image.”

As I said, photography was everywhere and necessary in the 60s, onward. The only remaining documentation of the ‘happenings’ and other conceptual art projects are photographs. But photography was also surviving for artists by its technical complexity, like the sculpture and printmaking that we studied in school. You can get intrigued in the acts of the making. Painting and drawing are such old arts that we forget they have technical complexity – but I think very contemporary paintings are trying to bring this back and make the statement – ‘see me, I was made by a human trying to say something.’ I see it as something that already been done, but I am intrigued by the effort to make a painting jump off a wall

This show, what the curators called Transgressions & Amplifications, reminds me that photographers back then felt the changes we now know. They needed to find new ways to say ‘made by human’. To use the curator’s ideas: they transgressed the boundaries between text and image, amplified the hand-made nature of their work. This push of the envelope of art photography by human means was a great step ahead for art. More like a primal cry than the smart use of technological advances. Edward Burtynsky makes great techy aerial photographs. But they feel intellectual, not emotional when compared to these early works made when the realistic (and physically printed) image was headed for the grave.

When old techniques are used, the artists in this show seems to be illustrating our mechanical history, the processes revealing more of the human hand. They are not nostalgic. It’s a post-modernist questioning of the past, and has that quirky post-modern humor. At its most fun when some time has gone by. For example, Betty Hahn printed everyday images using a very old technique and crafted them into pillows. Some of the everyday of then, of course, are historical now.

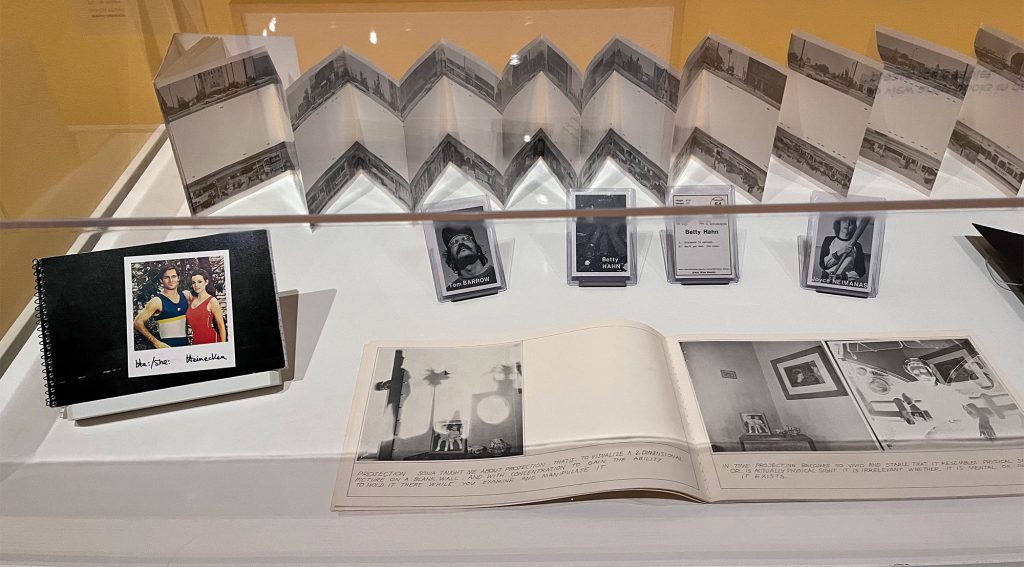

Ed Ruscha’s Sunset Strip is included as the epitome of documentation itself as art. Composition is what makes the emotion. Composition within the frame and also the aggregation of the strip onto an accordion-folded book. Books of My Life, made by Keith Smith, are a hidden gem I couldn’t see by looking into the glass case. I have no idea how many there are, but I’m putting in a request to read them. Robert Heineken captions his Polaroids (didn’t we all?). Another artist writes her life story on a photograph. Or, at least, that’s how I remember it.

Photos of the Exhibition

Betty Hahn, Soft Daguerreotypes, 1973. Xerographic images on fabric.

Photo of a TV dinner taken with Daguerreotype process, which produces a glass negative that was then used to make a Xerox copy onto fabric that was then stitched and stuffed.

Betty Hahn, Soft Daguerreotypes, 1973. Xerographic images on fabric.

Hahn used the 19-century Daguerreotype process on a copy machine to get the image on fabric. She framed them in the brass and velvet style commonly used on those old-timey photos. Instead of family, the images are the everyday: sticks, weeds.

Betty Hahn, Soft Daguerreotypes, detail, 1973. Xerographic images on fabric.

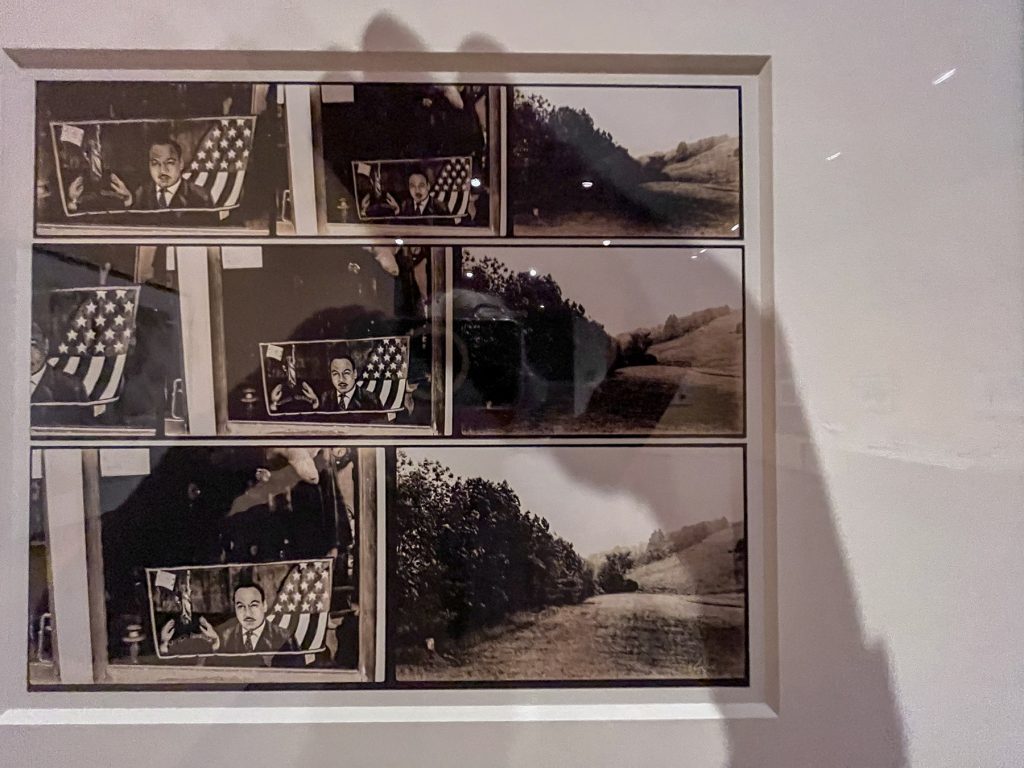

John Wood, Martin Luther King, Wellesville, New York, 1969. Kodalith print.

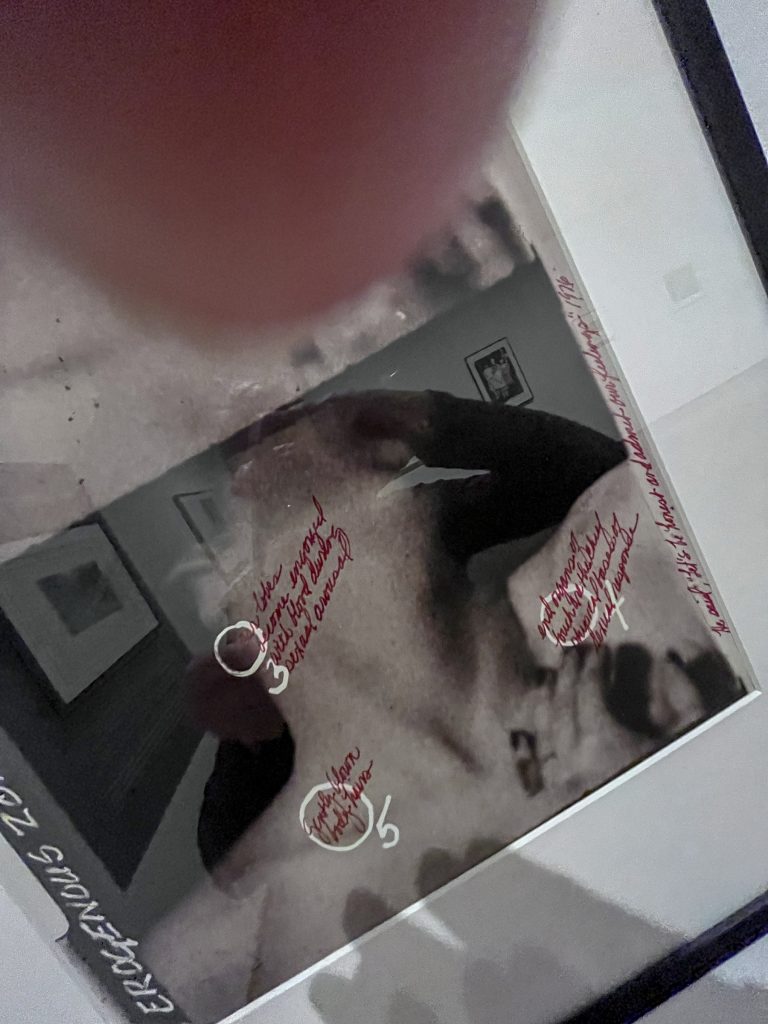

Joyce Neimanas Erogenous Zones of a Male #A-1, Neg. 2, 1976. Gelatin silver Print, with applied color, red ink. Snapshot taken from an erotic film.

(at right) Keith Smith, When I Was Two (Book68), Artist Book, Rochester Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1977 .

Robert Heineken, notebook (left); Keith Smith, Book32; Mike Mandel, Baseball Photographer Trading Cards , 1965. Offset Print (middle); Ed Ruscha, Sunset Strip (back).

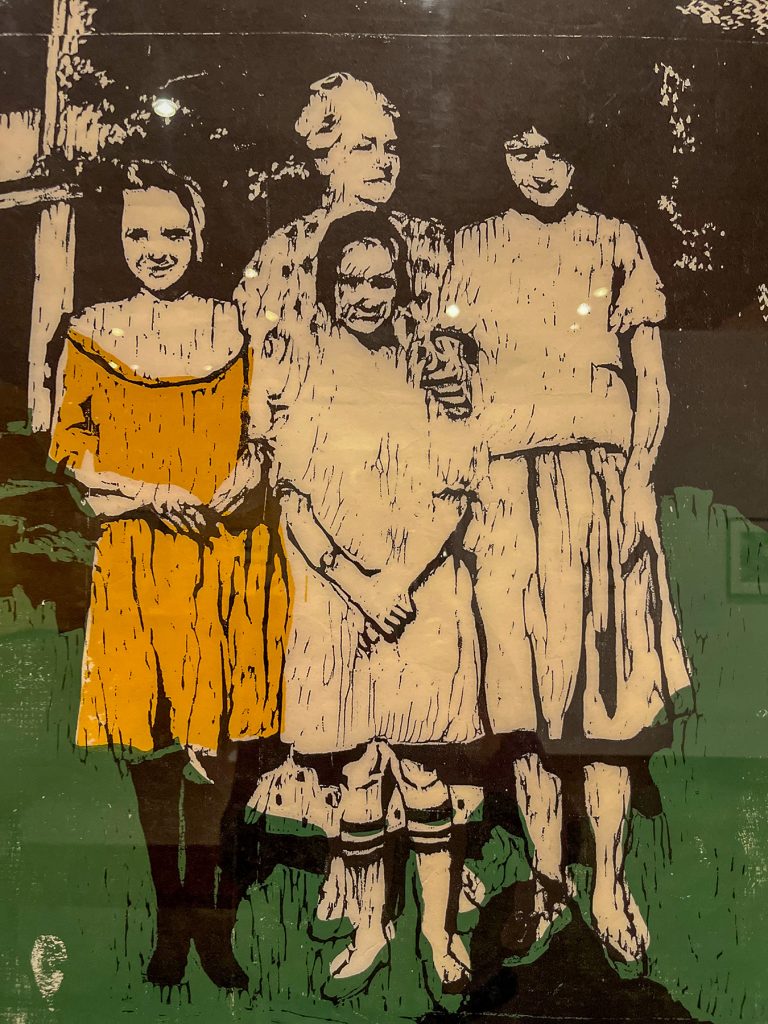

Betty Hahn, Someone Else’s Snapshot, 1965. Photographic woodcut.

Using a photo process, Hahn directly uses an old, classically-posed, family picture to make a traditional looking woodcut. She doesn’t try to make it groovy to depict that time she made it. There is no ego involved but an emphasis on the technique. Just making it a woodcut makes it feel hand-made and personal. The curators really that it was funny that Hahn pulls off this personal quality, and yet the image was from a found negative, not her own family.