An Art Tourist visits New in old town of Strasbourg

Konrad Klapheck is a shiny machine in an OK modern museum

by Terry Talty

Strasbourg, France – Great spaces but nothing to put in them – this seems to be the plight of the contemporary museum that wants to have a retrospective of not-so-old artwork. Happenings and other ethereal artworks of the recent past do not offer much to show except their documentation.

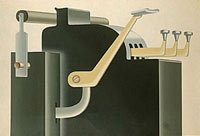

I walked a long way through the tall open spaces of the museum of modern and contemporary art in Strasbourg until I found the special exhibition, on until May, of Konrad Kapheck who happened to come from around there – Dusseldorf, Germany. He was a mechanical type of painter – but not a photorealist – a one-of-a-kind, true-to-his-guts-and-style artist. He was well educated in art and taught at university, so he is not a naive folk artist but a very skilled technical draftsman and painter. And he happened to live in Pop Art times. Just before painting was declared dead.

The work fits right into the cold, sleek modern building. Sleek and looking a touch like the furnishings.

Kapheck's work of a lifetime – from the 60s through today – is the work of a virtuoso of painting – mechanically – and stylistic monotone.

To emphasize color –add the lack of it – the show included framed pencil drawings Kapheck did of the subject before he painted it. These were black and white, very well planned out, and he'd left the pencil marks where heıd used a compass or other tool to make the shapes perfect.

As a tourist who loves looking at art, I read a key bit of curation – a remark on the wall from the artist himself who said he wanted to have his paintings look as if a machine had made them. Not an emotional human. I'm contemplating the spectrum of 20th C. painting from emotional expressionism to present day obsequious computer drawings, and want to place Mr. Kapheck pretty damn close to the computer. Then, I start reading the emotional human titles the artist gave to each one of the paintings – Of the Winters of the Feelings or Four Hearts in the Evening. The subjects of the painting carrying these titles are machines. Now, I have to move Mr. Kapheck slightly more to the expressionist side.

My companion of the day – an American land-artist – said he enjoyed seeing the drawings because they had a little more life than the paintings, which he felt were pretty life-less.

I think that's what he wanted, I said, pointing to the cards. I don't read French, he said.

³I liked the shapes he painted and his precision, but the paintings didn't overwhelm me. I tend to like stuff like this – clear and cartoony like (Roy) Lichtenstein's paintings.There was something flat about them, and did I have to read his intention to enjoy the work. The Painted Word, by Tom Wolfe comes to mind.

³It makes sense that Kapheck removed the painterlyness, but at the same time it was obvious a man had painted it. So he failed on his stated mission.

So, I'm going to ignore what I've read. Several painting was visually dynamic, with repeated patters, unusual and vivid. The painter – the man – seems to have a realtionship with some of these machines. The bicycle one had a perspective, too.

It would be hard to be emotionally struck by several rooms full of paintings by a machine.

The rest of the work upstairs in the ³contemporary² section was made by people artists and was even more stingy about giving any information to the viewer, though there were some shock-effect pieces. For example, a wall of sad obviously adult cartoons hung on the wall like a group of kids' drawings – sad kids.

Do we expect more of art that it should give? If one of the bits of a broken dish falls off a Julian Schnable, does it make any difference?

The museumıs collection

The museum nicely hung a series of paintings from early late 20th century art – I think the 80s. The work was a line of monochromatic canvases displayed so that when you walked along the center corridor and by openings -- glassless windows – you could notice the field of color had changed. In the room of his work you felt a little too close to the color. The rest of the artists work was a solid black or pure white canvas –the final statements of modern art – the jumping off point for postmodernism.

Below us was a whole floor of neo-classical to modern work collected by the town museum for a variety of reasons that would each make a pretty interesting story, but not a museum full of great art. One little note is that Jean Arp was from Strasbourg and a room of his sculpture stood out as a contemplator's heaven – a nice meditative space.

The contemporary exhibition space was big and cold – outside the building, the place was beautiful and the art cafe on the roof of the first floor was very pleasant with a very hard-working waitress who could have been a model for Maillol. She wore black and white and while not svelte, she moved very quickly and gracefully, holding a tray in a very competent way.

In a way, she made me realize human life is more compelling than machines, and that's why a work of art with figures moves us – and why it is easier to make a mistake – not hit the mark – with a work of art when it includes a figure. So when we paint machines, are we avoiding our race? Or is it just when we paint pictures of machines that are made to look like a machine painted them?