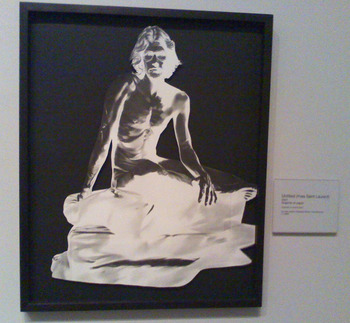

Robert Adams photographs at the Denver Art Museum are the spitting image of ones we've taken as young people exploring rural Colorado and beyond in the '70s and '80s. They are Black and White and make the jarring primary colors of the commercialism of that day look tolerable. And the landscapes beautiful. Like the romanticism of Pete Seeger, 'I am the blue of my sky and the brown of my earth.' And they make the same folksy protest, as well.

Robert Adams photographs at the Denver Art Museum are the spitting image of ones we've taken as young people exploring rural Colorado and beyond in the '70s and '80s. They are Black and White and make the jarring primary colors of the commercialism of that day look tolerable. And the landscapes beautiful. Like the romanticism of Pete Seeger, 'I am the blue of my sky and the brown of my earth.' And they make the same folksy protest, as well. We didn't and still don't want to see all the beautiful land in the West to be churned up and spit out as the same old shopping mall. Why not just leave it, and fix the old shopping mall? Well, because that land looks so easy, just lying there. Adams' photographs prove it.

His photographs of a common farm house on the plains of eastern Colorado looks wonderfully textured in black and white, the wall paper less busy with color and the people richly gray. He didn't make them to be nostalgic. He was just depicting life as it was, and it wasn't that easy. But, with hindsight, we can see that a lot more people were trying to keep that life than managed to do so. There were still a lot of small farms in Colorado, but everything was changing. Farmers only grew what they could sell to big companies. There were no farmers' markets in the city where they could sell anything else. And they had to buy Roundup.

We were, and still are, environmentalists. We wanted then, and still do want, organic food and clean energy. We environmentalists are the domestic terrorists that exPresident Bush warned everyone about. We personally may not have advocated burning private property on the Vail Valley ridgeline in the National Forest, as the ELF did when Vail Resorts was building Two Elk Lodge (in memory of the elk that used to be there). I, personally, wouldn't have had the nerve to do it, but I have advocated for less development, especially outside of established ski resorts. There are some who argue that Vail and everything within 25 miles of it, is already ruined. But there are people who thought the new development was the place to draw the line. And they were completely ignored.

Logically, the ski business is flat, so they don't need more property. And Two Elks was the opulent symbol of expansion by a Vail that couldn't be stopped. The frustration of people who see that Two Elks wasn't at all necessary for most Earthlings, is what prompts terrorism. A little arson at midnight, to a half finished building far out in the wilderness where there was no threat to human life or anything but the building - the symbol of wastefulness.

If you understand this frustration, the feeling of not being heard, you can imagine why an Arab might want to become a terrorist? Can you imagine how hard it would be to be heard in a kingdom where you are a subject and not a citizen?

Look at the people calmly viewing Robert Adams photographs and you will see them smiling. They want that peaceful landscape. Then the scowls -- people are bugged by the lost of citrus orchards in California. Orchards or shopping malls. People do want orchards. There are too many shopping malls between people and their orchards. Because now most of us live in the city.

Change isn't necessarily bad. But are we doing very much to figure out which change is good and which is bad?

Robert Adams photographs might be a place to start.

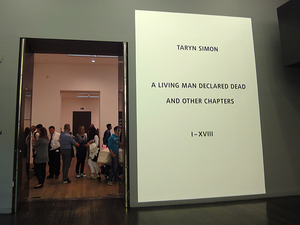

My goal is to pass beyond the guy at the podium and start my trip to England and beyond. 'What's the purpose of your trip?' the guy asks holding my passport. To see art, of course. Instead, I say 'visit family.' I want to slip in, look ordinary like my passport photo on its neutral background.

My goal is to pass beyond the guy at the podium and start my trip to England and beyond. 'What's the purpose of your trip?' the guy asks holding my passport. To see art, of course. Instead, I say 'visit family.' I want to slip in, look ordinary like my passport photo on its neutral background.

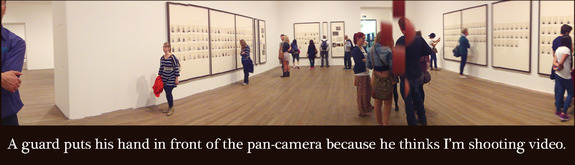

Look at the people in this exhibition. They're myopically reading the walls. Or standing in the center talking. One of our group suggests that Simon make it easier to read the narrative, and give us the time and space to read it - publish a book. Good idea, but her current audience is, right now, wandering through the Tate Modern. And, it's a big crowd, a less-than-mainstream crowd: people willing and able to look at contemporary visual art. Give us the visuals.

Look at the people in this exhibition. They're myopically reading the walls. Or standing in the center talking. One of our group suggests that Simon make it easier to read the narrative, and give us the time and space to read it - publish a book. Good idea, but her current audience is, right now, wandering through the Tate Modern. And, it's a big crowd, a less-than-mainstream crowd: people willing and able to look at contemporary visual art. Give us the visuals.