by Terry Talty

February 6, 2011

I'm a freelancer and - as my friend delicately put it - there's a gap in my schedule. Nobody loves you when you're down and out, so I hate to mention how down my financial future seemed to me last night. It could just have been the weather. Snowing for a week, no sun and frigid. So unDenver like. Snow, sure, but never without sun in between.

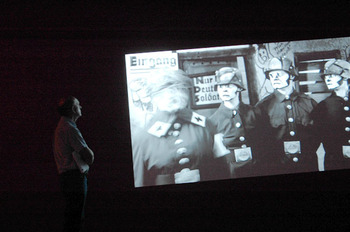

Anyway last night, I'm worrying about worldly things and I'm at an opening at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art. Tons of people mill around me to see the three new shows. In retrospect, I can name the three by the method of getting in your face: Bones, Blood and War.

On the entry level is the work of Dario Robleto in an exhibition called "An Instinct toward Life." I'm standing in the white, big gallery surrounded by small things, spaced far apart. Bone and other human parts went into the art objects - that's the buzz in the room. Such a provocative theme should provoke me to gush with ideas, but the few thought bubbles arising are my same old ideas.

The boxing gloves (pictured) are titled

The Melancholic Refuses to Surrender and reminds me why I hate boxing movies - the unnecessary pain of some sports. Broken male hand bones are just one of the listed ingredients in this piece and

The Hustler. A wine jug, called

The Skeleton Wine has a materials list that includes '

cast and carved bone, bone dust from

every bone in the body, ground wisdom teeth.' And 'homemade wine'.

Next to the wine jug are a collection of little pitchers the white card says were used to feed invalids - apparently a while ago before the invention of the IV - with the title,

"A Ghost Nurse Still Needs to Care." 'Made out of bone,' my friend, a sociologist says. Like bone china, I say.

I nearly trip over a pile of dinosaur and human bone dust on the floor as I dash off to a quiet corner to look out the window and take a phone call from my son. He's in traffic and I'm in a crowd and we can hardly hear each other. This happens more often than I want to remember and I promise to call him back. He promises to do the same and who knows what audio quality chance will give us next time.

I step back over the dinosaur and human dust. I do think, at that moment, about how my body might decompose and rejoin the earth after I'm dead. I've never been a fan of a niche in a cemetery. I want my dust to be spread on the garden just like my grandfather-in-law was added to his bean trench. I mentally follow my future remains through the ground, into Denver sewer system, down the Platte into the Gulf of Mexico, possibly reincorporated into fly, then fowl, into New Orleans chef. I feel disappointed, however, because these ideas were not new ones to me. I'd already used them for a short story.

When you get old, my uncle once said, you never have a new thought. You just recycle the old ones. Uhg.

In another corner, a pair of boots is standing in a pile of dust. Human bone dust, I guess. Inside each boot is a wooden leg. Carved by soldiers - amputees - my friend says - from the Civil War. I couldn't get close enough to the wall to read the card.

The curator, Nora Burnett Abrams, associate curator of the MCA, says the cards on the wall are poetry and invites everyone to read them. My sociologist friend says the artist told her he writes the cards first, then conceptualizes the physical work. He's into metal detectors, she says, he finds lead bullets and wedding rings on battlefields. Human ring finger bones are in the next room covered with some of this lead.

Are you cringing yet? Or are you feeling as ho, hum as I'm feeling?

Whether it's fair criticism or not, this show has failed to seize my brain, and get me out of my funk.

Look at the world I'm living in. A place that needs Payday Loan shops. Not that I have a payday in my future. If I go to work at McDonalds I'd have to work more than 62.5 hours per week to make $2000 which, cut by an immediate minimum 15% for taxes, would barely cover my half of the mortgage, my ever-rising health insurance, food and bills. And I couldn't work at McDonald's alone, I'd have to get another minimum wage job at Wal-mart because they won't let you work full-time. They'd have to pay your health insurance.

Imagine a mom and dad having to work this much. No way they could take care of their own kids or ever cook a meal. Or go to an art museum.

Sure, tonight was an opening, so it was free, but I still had to rifle through the change drawer to get the train fare. And have the time. And a couple of brain cells that aren't overloaded by responsibility and money trouble. When you're worried about your next job, or if you can ever settle your Pay-Day loan, you can't think about art or anything like it. You'd be lucky if you could hear a full sentence on one of the TVs that are constantly blaring at your workplaces.

I'm not criticizing the craft of the work. The artist has contrived each piece into a form that is a pleasing design. The ceramic jug doesn't look as strong as Wedgewood, but it doesn't need to be. It isn't intended to be functional. Nor am I sure I want to criticize the shock value he's going after by using human bone, hair samples and love letters. That artwork reaches to get someone's attention is not a crime. We're all required to do some marketing.

I'm just saying that a concept can't generate feelings that the artwork doesn't corroborate.

Because each of Robleto's handmade objects is small, each has a natural intimacy. I should start to have a connection to the humans that might have used such a thing, but he add the same distance a history museum can't quite eliminate. He lines up the invalid feeders on rows of shelves, has a kaleidoscope pointing to the man/dinosaur dust, hides braided human hair flowers in a giant nest of craft-project paper flowers.

And then, there's the poetry. On the jug in The Skeleton Wine is an inscription "Scrubbing Your Soul Won't Make it Clean," and the following materials list:

Materials: cast and carved bone, bone dust from every bone in the body, ground wisdom teeth, homemade wine (water, sugar, fermented grapes, black cherries, plums, red raspberries, yeast, gelatin, tartaric acid, pectinase, sulfur dioxide, oak flavoring) fortified with calcium, potassium, creatine, zinc, iron, nickel, tin, copper, boron, vitamin K, crushed amino acids, glutamine, chromium, sodium, magnesium, colostrum, phosphorus, iodine, microcrystalline cellulose, quartz, rust, water extendable resin, typeset, driftwood shelf.)

What difference does it make if there is wine in this jug or not? We can't see it. We have to trust the artist that he has actually used any of the listed materials. It's a leap of faith and I'm not sure why I'm being asked to take this leap so that I can look at these materials in the new forms that this artist has made. Am I to scrub my soul with homemade wine and the blood of Christ, and still have to grab for the Comet?

If the artist is trying to inform me - explain what it takes to make wine - it's a self-serving attempt to gain my trust.

If the objects are made to deliver poetry in cleaver titles, then does that work?

The piece,

A Defeated Soldier Wants to Walk his Daughter up the Aisle - the boot - is made with wooden legs that Civil War amputee soldiers carved for themselves, the card verifies when I finally have a chance to read it. And the boots are World War I standard issue. I'm not trying to be a stickler for accuracy but when things don't fit logically they lend themselves to comedy. According to philosopher, Noël Carroll, incongruity is at the heart of all jokes. The titles makes the campy object a joke. Like a fraternity trophy used as a beer stein.

What gives me the most outrage is that Robleto has somehow sucked the ink off soldiers letters home and made them into dye for one of the pieces shown here. Maybe the soldier was a bad writer, but if I was his/her kid, I'd want the letter.

The arrogance of the artist, thinking that someone would wish their bone or their ink anonymously included in his ceramics or paper-making projects, is glaring.

I'm usually as willing to laugh at campy stuff as the next Post Modernist. Tonight, however, I feel like such an ordinary Joe, weighed down by real or imagined financial worries, that I'm not sure I'm the most open observer. Like an ordinary observer, I feel outside. And from here, it looks like too much of contemporary art is an inside joke.

Terry Talty, who

writes this blog, pleas for forgiveness for being a downer: Please do

read the next installment, which is sure to be more optimistic. Sign up

for the RSS feed, if you can spare the time.

The clean sparse naturally lit sculpture center in Dallas, created by the 20th C. collector moguls Raymond and Patsy Nasher, shows Tony Cragg's 21st C. sculpture like they were made for each other.

The clean sparse naturally lit sculpture center in Dallas, created by the 20th C. collector moguls Raymond and Patsy Nasher, shows Tony Cragg's 21st C. sculpture like they were made for each other.

Cragg's work is slick and purposeful, but so detailed it could only have been made by Computer-Aided somethings: like software and router, cutters and pointing-up devices. They are assembled by some kind of careful, aesthetically superior being(s).

Cragg's work is slick and purposeful, but so detailed it could only have been made by Computer-Aided somethings: like software and router, cutters and pointing-up devices. They are assembled by some kind of careful, aesthetically superior being(s).

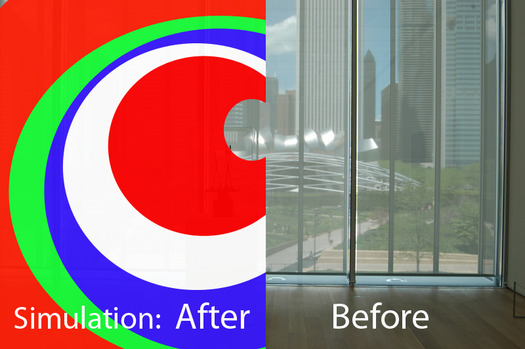

Victory

over the Sun

is the title of a 1913 Russian opera.

Victory

over the Sun

is the title of a 1913 Russian opera.  Learning to step into the shade was my first victory over the sun. Is this show about how man's ingenuity can beat nature's unpleasantness? Or do we need to know the art history themes attributed to the first Victory Over the Sun to get this show?

Learning to step into the shade was my first victory over the sun. Is this show about how man's ingenuity can beat nature's unpleasantness? Or do we need to know the art history themes attributed to the first Victory Over the Sun to get this show?

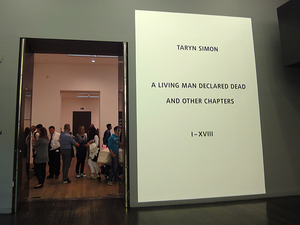

My goal is to pass beyond the guy at the podium and start my trip to England and beyond. 'What's the purpose of your trip?' the guy asks holding my passport. To see art, of course. Instead, I say 'visit family.' I want to slip in, look ordinary like my passport photo on its neutral background.

My goal is to pass beyond the guy at the podium and start my trip to England and beyond. 'What's the purpose of your trip?' the guy asks holding my passport. To see art, of course. Instead, I say 'visit family.' I want to slip in, look ordinary like my passport photo on its neutral background.

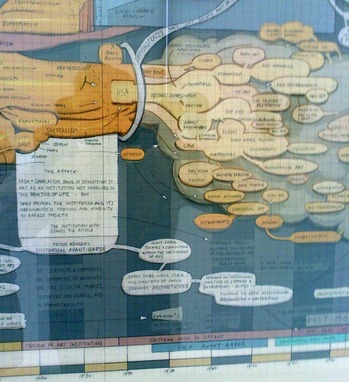

Look at the people in this exhibition. They're myopically reading the walls. Or standing in the center talking. One of our group suggests that Simon make it easier to read the narrative, and give us the time and space to read it - publish a book. Good idea, but her current audience is, right now, wandering through the Tate Modern. And, it's a big crowd, a less-than-mainstream crowd: people willing and able to look at contemporary visual art. Give us the visuals.

Look at the people in this exhibition. They're myopically reading the walls. Or standing in the center talking. One of our group suggests that Simon make it easier to read the narrative, and give us the time and space to read it - publish a book. Good idea, but her current audience is, right now, wandering through the Tate Modern. And, it's a big crowd, a less-than-mainstream crowd: people willing and able to look at contemporary visual art. Give us the visuals.

Anyway last night, I'm worrying about worldly things and I'm at an opening at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art. Tons of people mill around me to see the three new shows. In retrospect, I can name the three by the method of getting in your face: Bones, Blood and War.

Anyway last night, I'm worrying about worldly things and I'm at an opening at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art. Tons of people mill around me to see the three new shows. In retrospect, I can name the three by the method of getting in your face: Bones, Blood and War. I step back over the dinosaur and human dust. I do think, at that moment, about how my body might decompose and rejoin the earth after I'm dead. I've never been a fan of a niche in a cemetery. I want my dust to be spread on the garden just like my grandfather-in-law was added to his bean trench. I mentally follow my future remains through the ground, into Denver sewer system, down the Platte into the Gulf of Mexico, possibly reincorporated into fly, then fowl, into New Orleans chef. I feel disappointed, however, because these ideas were not new ones to me. I'd already used them for a short story.

I step back over the dinosaur and human dust. I do think, at that moment, about how my body might decompose and rejoin the earth after I'm dead. I've never been a fan of a niche in a cemetery. I want my dust to be spread on the garden just like my grandfather-in-law was added to his bean trench. I mentally follow my future remains through the ground, into Denver sewer system, down the Platte into the Gulf of Mexico, possibly reincorporated into fly, then fowl, into New Orleans chef. I feel disappointed, however, because these ideas were not new ones to me. I'd already used them for a short story.  In another corner, a pair of boots is standing in a pile of dust. Human bone dust, I guess. Inside each boot is a wooden leg. Carved by soldiers - amputees - my friend says - from the Civil War. I couldn't get close enough to the wall to read the card.

In another corner, a pair of boots is standing in a pile of dust. Human bone dust, I guess. Inside each boot is a wooden leg. Carved by soldiers - amputees - my friend says - from the Civil War. I couldn't get close enough to the wall to read the card.