February 24, 2011

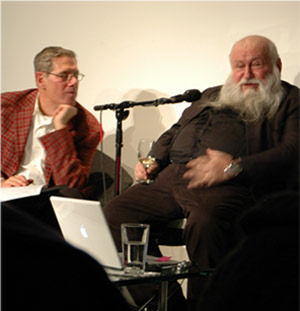

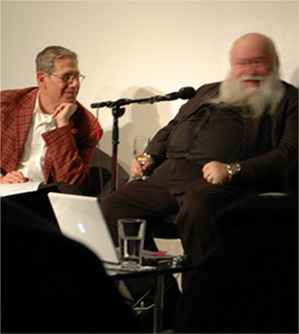

February 24, 2011A massive body clad in black circled with a mane of a white beard, Hermann Nitsch is more than 70 years old, and the audience listened to him talk Thursday night at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver treating him with reverence.

The audience jibed familiarly with MCA director Adam Lerner as he introduced Nitsch, whose half dozen paintings and dozen religious vestments are on exhibit in the museum. Warmly, but casually, they greeted the team of interviewers: Patrick Greanley, a European literature scholar, and curator Simon Zalkind. The audience hushed to hear the artist speak.

The Austrian started in English and when he got rolling switched to German, and Greanley peddled hard to deliver the translation quickly and unobtrusively.

Zalkind asked questions I wanted to ask and with an intelligence I wished I had. My repetition of these questions is such a weak approximation: How did Nitsch get the idea to use performance so early, in the'60s? How was Nitsch influenced by Abstract Expressionism (a largely American movement important in the 1950s)?

Zalkind asked questions I wanted to ask and with an intelligence I wished I had. My repetition of these questions is such a weak approximation: How did Nitsch get the idea to use performance so early, in the'60s? How was Nitsch influenced by Abstract Expressionism (a largely American movement important in the 1950s)? It wasn't so much what Nitsch said -- he listed influences like Mallarme, Pollack, deKooning, many names that most audience members could pick out from the man's German with a good amount of effort -- it was the way he barely moved as he delivered the answers. And was rewarded with an odd reverence and hush. When he said Freud and Jung and John Cage, we felt we could lighten up. He'd sounded so ethereal, eclectic, and then it was obvious, performance comes from John Cage. This guy was part of the ordinary consciousness of his time. Then he names his special influence -- spirit. Not the kind bound to any religion, but the spirit that drives action. Then Zalkind pressed him on the weird nature of his form of self expression and Nitsch talked more about the all-encompassing power in humans and how it is bound too tightly by civilization. He's about unleashing all that human power.

Zalkind asks about Catholicism. Nitsch answers 'I was educated as a Catholic, but maybe not so well.' The audience laughed. Were allowed, by this point, to laugh with him.

Zalkind asked if intensity is necessary? And Nitsch light on fire. Yes. The intensity of smearing feces - he invokes Freud -- not that this act is not actually part of Nitsch's work -- but intensity is absolutely important. His intensity is making a ritual for six days where the participants act animalistically smearing blood and paint over themselves and the canvas on the floors and walls, or so it appeared from photographs. The theatre if a Mystery Orgy theatre, after all.

He goes on about: the intensity of Tao. The intensity of grass growing. The guy is bi-polar intellectually: earthly and ethereal. And we've all got our ears peaked up to try to make out what really is the answer.

A moped and Chrysler, he said, when asked if the paintings are art on their own, or does a viewer really need to be a participant in one of the Orgy Mystery Theater performances. The paintings are merely documentations of the act of the theater. And the theater is just a release of some human power, a diversion from how it could be released violently with worse effects to humanity, but instead is a release that empowers each participant. How does it do this? We don't get the answer.

Does the exhibition do this? The flowers in the room smell. The blood in the paintings has dried brown on the canvas, been layered under red paint and been stamped with foot prints. You'll have to add the intensity yourself. I want to taste the blood. I want to see the theatre.

The paintings are the moped, Nitsch finally said. The event is the Chrysler, and we're all invited to participate in his next event in the summer of 2013 in Austria.