Looking for the Face I had before the world was made

by Terry Talty

January 30, 2010

DENVER, COLORADO - Representing the human face in art is a little like telling everyone who you're sleeping with. You're admitting what you find attractive (akin to buying unusual art - you must like this weird thing - it says to anyone who might see it in your house).

When you paint heads, you're showing what you think is human. If you paint with accuracy and copy every detail of a face, you're placed in a sub-genre: photorealism, or worse portraiture. Like the artist/photographer in the neighborhood portrait studio, you're an artist with the narrow vision of seeing just one face. And this is a valuable mission when you're hired by a high-school senior to make something for the yearbook. It's a different mission to paint what you want to represent humanity. Many contemporary artists use a cartoon, a symbol, or some other kind of messy mark or gesture to depict the every-face. Michaël Borremans blur some, and focuses well on the nondescript parts as he works to find another way to that universal face.

The show called Looking for the face I had before the world was made is six-different exhibitions by six artists that opened Jan. 29 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Borremans' paintings, about 10, are in the main floor gallery.

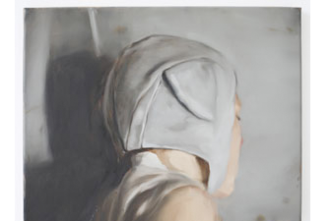

The faces in the paintings are not engaging the viewer. We are looking from the back of heads, at someone looking away, at the profile of an artist intent on something oblique to us. The colors are somber and in one, the subject is a thorny stick leaning against the wall. In one, the figure is wearing a tight cap that seems to have mouse ears sewn onto it.

'No one would be caught dead in such a hat unless it was a costume, says my friend, nudging me. My friend has the rare profession today of being a housewife.

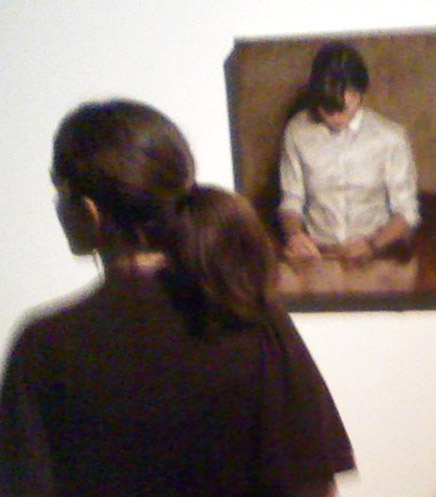

The universal face is on the other side of that hat, looking into the picture frame with us. But as my friend said, that hat is drawing our attention to her - the feminine subject. Inside another frame is a brown-haired feminine subject looking down at her hands. No facial features stand out. Two figures are standing in the dim gallery light looking at this canvas. One brown-haired female looks like the painting. I take her picture on my crummy phone camera. The other human is a guy with too much apparent individuality to be the universal. One side of his head is shaved and the other - I can only see a dark line of hair at the crown from my vantage point - seems to be the barbershop classic, the taper.

The universal face is on the other side of that hat, looking into the picture frame with us. But as my friend said, that hat is drawing our attention to her - the feminine subject. Inside another frame is a brown-haired feminine subject looking down at her hands. No facial features stand out. Two figures are standing in the dim gallery light looking at this canvas. One brown-haired female looks like the painting. I take her picture on my crummy phone camera. The other human is a guy with too much apparent individuality to be the universal. One side of his head is shaved and the other - I can only see a dark line of hair at the crown from my vantage point - seems to be the barbershop classic, the taper.Try to mentally draw this threesome as the universal. The guy can pose showing his left or right side and play the part of twice as many characters.

I let Photoshop help me try to find the 'common human.' I eliminate until I get there, worry I've taken away to much, or kept too much. When I'm done, I'll mentally put this face, these faces, in a scene that we all do: look at our hands, scratch an itch or turn away from someone looking at us. Give it a try, and then come back and look at these paintings.

The primordial human face -- one to whom we can all relate -- is cold and sad like the feeling in this gallery. We are not inside this human. We are looking at it from a separate skull. The feeling is completely different feeling than the Renaissance window to the world where we look into a picture and buy the illusion, as if it's a window onto a painted scene.

I'm pretty sure Photoshop and I have a long way to go before we finally create the meta-face, but when I look back at the Borremans painting where that I was trying to understand in that exercise, I notice they are not like the open magazine painting. They don't prompt me to feel 'hey, we're all looking at the same stuff. I can really feel I'm seeing with that figure's eyes.'

Instead, I question, 'hey, is that what I look like to the world?'

The name of this exhibition, of which these paintings are just one part, is "Looking for the Face I Had Before the World Was Made," taken from a line in a poem was W.B. Yeats. And if Borresmans has found the face that we had before the world was made ... have I always looked that alone?